UPDATE: According to Ken Rosenthal, the MLBPA and commissioner’s officer are still trying to determine the AAV of Derek Jeter’s new contract, but the likely range will be $12.8 million to $13.2 million. Where does that figure come from? Rosenthal cites “reasons too complicated to explain”, but my best guess is it’s the new $12 million base salary plus a proportional amount of under-reported AAV from 2011 to 2013, the origination of which is explained in detail below.

The Yankees just announced that Derek Jeter signed a one-year, $12 million contract extension, which, according to whom you trust, is either a very savvy financial decision with luxury cap implications, or a bewildering ode to legacy.

According to Joel Sherman, the new contract increases the average annual value of Jeter’s contract from $10.75 million to $12.8 million. However, Sherman has not yet responded to calls for him to show his work. Considering his well placed sources, it could be that Sherman’s figures were provided by the Yankees, but absent such an explanation, they do not seem to square with the tenets of the CBA.

Derek Jeter’s Prior Contract Breakdown

Source: Cots baseball contracts, CBA

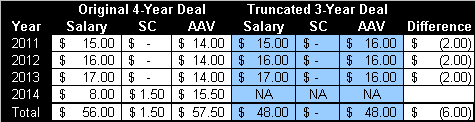

Here’s what we know about Jeter’s contract. The original terms called for three years (2011 to 2013) with salaries of $15 million, $16 million, and $17 million. In addition there was a player option year valued at $8 million with special covenant clauses that would lead to an escalation. Finally, Jeter had the option of exercising a $3 million buyout, which would have terminated the 2014 player option. With those irrefutable facts on the table, we can now turn to the CBA.

Article XXIII Section E, Part 2

Average Annual Value” shall be calculated as follows: the sum of (a) the Base Salary in each Guaranteed Year plus (b) any portion of a Signing Bonus (or any other payment that this Article deems to be a Signing Bonus) attributed to a Guaranteed Year in accordance with Section E(3) below plus (c) any deferred compensation or annuity compensation costs attributed to a guaranteed Year in accordance with Section E(6) below shall be divided by the number of Guaranteed Years.

Without the 2014 option, this section would clearly define Jeter’s AAV as $48 million divided by three years, or $16 million per season. However, we need to account for that nebulous fourth year. The first question to ask is whether or not it is considered guaranteed. On this, the CBA seems clear.

Article XXIII Section E, Part 5a (ii)

Player Option Year shall be considered a “Guaranteed Year” if, pursuant to the Player’s right to elect or subject to his right to nullify, the terms of that year are guaranteed within the definition in Section A(8); provided, however, that a Player Option Year shall not be considered a Guaranteed Year if the payment the Player is to receive if he declines to exercise his option or nullifies the championship season is more than 50% of the Base Salary payable for that championship season.

The key part of the passage above is the 50% rule. Because Jeter’s buyout of $3 million was less than 50% of the $8 million base salary, the CBA states it is considered guaranteed. In other words, both the base salary and year must be added to the AAV calculation. The result is a four-year deal worth $56 million, or an AAV of $14 million.

Article XXIII Section E, Part 4b

A Special Covenant in a Uniform Player’s Contract that provides that Player performance or achievement in one year of the Contract will increase the Base Salary in other year(s) of the contract shall not be considered in the determination of Salary until the triggering event occurs (other than, if applicable, as a “potential bonus”), unless it is determined by the Arbitration Panel that the Special Covenant was designed to defeat or circumvent the intention of the Parties as reflected in this Article XXIII. As long as such a finding is not made, the additional Base Salary triggered by the Special Covenant shall count as part of the Player’s Salary in the Contract Year(s) to which it is attributed by the Contract once the triggering event has occurred. Multi-Year Contracts shall not be recalculated on an Average Annual Value basis once the triggering event has occurred; the additional Base Salary shall be added to the Salary as originally calculated for the Contract Year in question.

What about those special covenants? The CBA clearly states that the relevant increase is applied in the year in which it is paid. Over the first three years of the deal, Jeter achieved one of the benchmarks (2012 Silver Slugger), increasing his 2014 base salary by $1.5 million. As a result, in the upcoming season, Jeter would have cost the Yankees $15.5 million toward the luxury tax calculation (his base AAV plus the special covenant payment). If this interpretation is correct, that’s the starting point for evaluating the Yankees’ new contract with Jeter.

Article XXIII Section E, Part 5d

If a Player fails to exercise or chooses to nullify a Player Option Year that is deemed a guaranteed Year pursuant to Section E(5)(a)(ii) above, the difference between the amount paid to the Player under his Contract (including any Option Buyout payment) and the amount that has been attributed to Actual Club Payroll of a Club under that Contract shall be added to (or subtracted from) Actual Club Payroll in the Contract Year in which the Player Option Year falls. If the Contract has been assigned, the adjustment called for in the preceding sentence shall be made to the Actual Club Payroll(s) of the Club(s) to which Salary under that Contract had been attributed in any Contract Year.

Had Jeter opted out of the previous contract, it would have likely cost the Yankees a $9 million underpayment penalty (see link for details). However, he didn’t, so we can put aside that scenario. Instead, Jeter seemingly nullified the option by neither exercising the extra year nor accepting the buyout. As a result, the Yankees wound up paying Jeter $48 million for three years, which brings us back to the original AAV of $16 million derived before considering the fourth year option. However, if the Yankees had been reporting an AAV of $14 million, that means they underpaid by $6 million (or $2 million per season). Section E, Part 5d seems to suggest that the Yankees would have to apply that amount to their 2014 payroll, which, combined with Jeter’s new $12 million salary, would create a much larger $18 million luxury tax hit. Or does it?

In the second part of the section above, it refers to “assignment”? Does Jeter’s decision to forgo consideration for his option year and re-sign with the Yankees fall under this umbrella? If so, the Yankees seemingly would have to pay the $6 million penalty in arrears as opposed to going forward. Under this assumption, the Yankees would be hit with a retroactive penalty (the luxury tax in each season multiplied by the $2 million AAV adjustment), but the 2014 AAV for Jeter would be reduced from $15.5 million to $12 million.

Is this interpretation correct? The CBA is an arcane document, but the passages cited above seem to suggest there may be a method to the Yankees madness. Of course, that’s not exactly good news for Yankee fans. If the team is robbing Paul to pay back Peter, it probably means the organization’s cost cutting plan remains in effect. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make sense for the Yankees to pay Jeter an additional $2.5 million in real dollars up front (as well as a retroactive penalty) for luxury tax relief in 2014. In that sense, Sherman’s explanation is probably the better harbinger because it might indicate that the Yankees are back to their free spending ways.

While most NBA teams hold contracts valued in excess of the salary cap, few teams have payrolls at luxury tax levels. The tax threshold in 2005–06 was $61.7 million. In 2005–06, the New York Knicks ‘ payroll was $124 million, putting them $74.5 million above the salary cap, and $62.3 million above the tax line, which Knicks owner James Dolan paid to the league. Tax revenues are normally redistributed evenly among non-tax-paying teams, so there is often a several-million-dollar incentive to owners not to pay the luxury tax.